Saintsception

Originally published at Stay Classy in February

This has been a long time coming. It’s time… to blog about Saints Row. Specifically, the latest game in the series, Saints Row 4. We’re going to get there in a roundabout way, however, so bear with me until this is over.

I want to talk about how Saints Row 4 is a game, about games, about games. If you’re interested in hearing more about this topic, feel free to join me after the cut. Definite (though not Earth-shattering — puns!) spoilers for Saints Row 4 and potentially for Saints Row: the Third ahead.

So yesterday games scholar Miguel Sicart spoke at MIT on his way to Indiecade East in NYC this weekend. I’m a big fan of Miguel’s work and he’s a super cool guy so it was great to hear him talk. I’m going to link the audio/liveblog of his talk here because I think it’s worth your time to listen to (and it runs around 90 minutes). I actually am going to suggest you listen to it before you finish this blog post, because I think Miguel’s concept of “quixotean play” is really vital to understanding what I’m going to say, but I know not all of you have 90 minutes, so I’ll give you the abbreviated version.

Miguel talked about a kind of play inspired by Don Quixote, a resistant and rebellious sort of play. Rather than accepting the rules of a system as they are, quixotean play emphasizes creating our own space for meaning. As I said, I’m being intensely reductive here for the sake of brevity; I really encourage you to at least read the liveblog of Miguel’s talk for deeper info.

Now, in terms of understanding games, I feel like game studies and critics in particular have started to use “play” really heavily, without strongly defining it, because we have developed this intense opposition to the word “game” as a way to define what we want out of our experiences. And I am not necessarily against moving away from “game” and toward “play” on the surface of it, however I feel like we’ve come to really overemphasize transgressive play and to overvalue people who “break the system” in some way. So I was on board with what Miguel was saying, but a question really germinated in my mind: where’s the space for pleasurable submission to the system in Miguel’s model (a model he specifically calls “a rhetoric of play” and not an all-encompassing definition) of “quixotean play?”

And when I was trying to frame that question for him, where did I end up?

I ended up at Saints Row 4.

If you want to hear the entire audio of my question to Miguel — and his answer, which I think was absolutely spot-on — skip to about the 1 hour, 15 minutes mark of the recording. But again, I’ll give you a quick summary for the sake of speed — I described Saints Row 4 as a game which takes place in a simulated VR environment, where your goal is to “break” the simulated VR environment by “breaking” (more bending) its rules, but doing so is a function of you, the player, submitting to the rules of the game’s simulation of the simulation.

One of my CMSW colleagues, Sasha Costanza-Chock, paraphrased my words thusly on Twitter:

.@laevantine 'There's pleasure in submitting to the machine to not submit to the machine to submit to the machine' #CMStalks

— Sasha Costanza-Chock (@schock) February 13, 2014

I think that’s pretty apt.

I brought up Saints Row here because, to me, it initially felt like the antithesis of quixotean play as Miguel laid it out. I mean, isn’t SR4 a game that pays lip service to the idea of rebellion by giving you the illusion of rebellion via the game’s fiction, while simultaneously asking you-the-player to submit entirely to its constructed universe? Yet for me, I find the game incredibly engaging and, more to the point, surprisingly liberating, because for me the joy is not from “rebellion” but from making meaning out of the system I was placed in on my own terms. And this is, believe it or not, the plot of Saints Row 4 made manifest.

In this game you are literally trapped in a system that you must reclaim to accomplish your goals, and you do so by carefully negotiating the system, slowly bending it to your will. This is important: while the Boss spends SR4 trying to subvert the simulation, they can’t do it outright. Though characters like Kinzie and Matt Miller can bend the simulation through hacking to give the Boss super powers…

…or a gun that fires lethal dubstep…

…those abilities are also part of the simulation, and only work inside the simulation. There are plenty of moments when the Boss needs to leave the simulation and shoot some aliens in meatspace, and all those nifty toys are for the most part gone.

Now, calling attention to the fact that the player is playing a video game is not a new thing for the series. For example, in SR3 when Shaundi asks the Boss “how long do you think this’ll take?”, the Boss responds: “I dunno. About two waves of SWAT guys?” (a measure of time that proves to be accurate). But SR4 in particular moves on to a new level of meta-commentary. It is fundamentally a game about the experience of playing a game. And this isn’t just about the series’ use of media tropes and in-jokes to get a laugh, though those certainly don’t hurt. I once joked that “Saints Row 4 is the best Mass Effect game I’ve ever played” and that’s only partially kidding; one of SR4‘s defining comedic touches, to me, is the hilarious sendup of Bioware-style romances, as this video should make pretty clear:

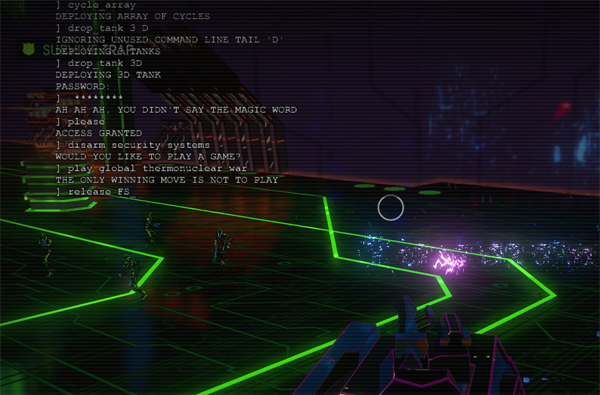

Never mind the tongue-in-cheek nod to ME‘s paragon/renegade choices you can see in this page’s poster image. I seriously could go on and on and on about this. The Matt Miller rescue mission is a weird fusion of Tron and the Atari 2600 Combat game, right down to the block-firing tank and the top-down view. Johnny Gat’s rescue mission is a cleverly-constructed 2D brawler sendup of Streets of Rage (called “Saints of Rage”) using heavy graphics filters on the in-game engine. Johnny even jokes later that “It’s weird seeing things in three dimensions again.” Asha’s rescue mission is a weird mix of Goldeneye and Metal Gear Solid. And so on, and so on. The list of gaming homages that fill SR4 are too vast to count and many of them can also be found in Saints Row: the Third too. But the homages and references are just the tip of the iceberg.

SR4 is fundamentally a game about the experience of playing games in the triple-A market right now, but it is a game that I believe encourages us to have hope that this experience that we as critics have come to dread is not necessarily all bad. It is a game that entirely acknowledges the rigid constructedness, the intertextuality of games as we understand them right now, but it is also a game that says “a certain degree of freedom within that structure can be meaningful.” In Saints Row I can be a curvy woman of size with prom queen hair and the ability to hurl people into buildings with my mind, and every single piece of clothing in the world I could find will fit me. If I want to get oral sex from an R2D2-knockoff robot with a mysteriously PUA-style sex pad on our spaceship, I can. It is a game that makes absolutely no attempt to wallpaper over its constructed nature, its limitations, but it’s also a game that says there is pleasure to submitting to those limitations.

I say that this is a “game about games about games” because I want to contrast it to one of AAA gaming’s most tired rhetorical stingers in the past few years: the “it was you the whole time” bit, the Spec Ops-style “you were complicit in this tragedy from minute one” nonsense. I find these sorts of meta-commentary games, these attempts to make us feel reflective on — or more accurately, feel bad about — engaging with them, to be really dull because they don’t offer any other alternatives for engaging them. Even The Stanley Parable does this at some points, mocking you mercilessly for doing the very things it asks you to do, though I am willing to forgive it more because TSP at least gives the idea of resistance some play, even if it does so by connecting “resistance” with “engagement-shattering inactivity” in a lot of cases.

Saints Row, on the other hand, never tries this. Rather the opposite: it throws its video game-ness in our face from the word “go” and then says “As long as you’re here, go nuts out there. Enjoy. We’ve peppered the requisite list of things you have to do with plenty of things you might want to do.” Even the fiction elements, the frame story of the Third Street Saints as a street gang, plays in: you’re not a hero, you’re (as the Boss puts it when Zinyak calls them a sociopath) a “puckish rogue.” The Saints are a gang. Running over pedestrians at will, firing rocket launchers into a crowded clothing store, using pro-wrestling moves on the police just for kicks: everything’s fair game.

And really, the idea of ‘state power’ is sort of problematized in this series anyway. Members of the government in the Saints Row world are almost universally either corrupt, comically inept, or just as bananas as the Saints (looking at you, Mayor Burt Reynolds). Police in Stilwater and Steelport will open fire, shooting to kill, if you bump their car with yours on the street. When STAG invades Steelport in Saints Row: the Third they are just as destructive and problematic as any of the city’s criminal gangs. Never mind the fact that in Saints Row 4 the Saints literally become state power. The main character is the goddamned President of the United States and that changes effectively nothing of how the Saints operate.

And this sort of liberating, everyone-is-terrible-but-not-in-an-ambivalent-Bioshock-way set up means that as a character, the Boss is a siege engine: you throw them against a problem and that problem gets solved, one way or another. It doesn’t matter how. In fact, the more ridiculous the eventual method, the better. The Boss never feels bad about anything and by proxy, neither do you. There’s a lot more to say about Saints Row‘s lack of judgment — which is present but not perfect — in terms of things like gender, sexuality, and body image but that’s a topic for another day.

To wrap this up: Miguel’s answer to my question inspired by Saint’s Row — about if there’s a place for submission in the resistance/rebelliousness of quixotic play — was actually quite satisfying, to me, and I think it encapsulates why I enjoy Saints Row and don’t enjoy things like Spec Ops: the Line or Hotline Miami.

Miguel argued that willing submission does not necessarily destroy the autotelic (self-driven) nature of play. As he put it, “we are negotiating what type of submission we are going to engage with.” I feel like Saints Row exemplifies this. It presents me with slyness, with a wink and a nod, but that’s a gesture that says we share this understanding of the limitations of the simulation, that we are equally complicit in my submission to it. And from that shared understanding, they build a playground where I can turn my submission to the system into something personally meaningful, if occasionally ephemeral. I can create moments of my own will, using the game as a toolbox, that are expressive, and sometimes even resistant, without necessarily positioning myself as opposed to the system.

In Saints Row: the Third I am obsessed with proper parking. When I drive to a place in that game I go as fast as possible, I drive in the opposite lane, I hit other cars and kill pedestrians, but when I get where I’m going, I am obsessed with finding a proper alley or street parking spot and carefully wedging my vehicle into it. That sort of obedience isn’t necessary, or even encouraged, but it’s allowed. And that’s something I don’t feel like those other games give me. Their options are “participate, or don’t.” That’s a choice that’s not a choice at all.

So in the end, I think I’ll continue to tilt at this particular windmill. Saints Row is my dom, I guess. But if pleasing it also pleases me, I’m happy to do it.

Originally published at Stay Classy in February