That Time I Escaped from Alcatraz

Thank you, Russ Enlow. There are so many horror stories from American gym classes, filled with shaming, and disgusting power dynamics, and negligent supervision, but not so for me. I know, I’m lucky. In my game studies circles I’m often the torch bearer for the benefits of athletics and physical education, not just in promoting healthy lifestyles, but also in developing teamwork, encouraging cooperation and communication, and fostering positive approaches to competitiveness. But it can often be an uphill battle when arguing in light of the many examples of the dysfunction of physical education in America. This post is not meant to argue that all physical education is well executed, nor meant to boast about my positive experiences, nor meant to invalidate any negative experiences people had in gym class. I am writing this post to share a positive example of physical education curriculum, and to open the door for discussions about how some of the principles and approaches in this one Physical Education exercise could be applied to other educational game endeavors, digital or otherwise. In this post I will recount my experiences with one specific game we played, and to make sure I got the details right, I got in touch with my teacher who designed the game.*

Thank you, Russ Enlow. There are so many horror stories from American gym classes, filled with shaming, and disgusting power dynamics, and negligent supervision, but not so for me. I know, I’m lucky. In my game studies circles I’m often the torch bearer for the benefits of athletics and physical education, not just in promoting healthy lifestyles, but also in developing teamwork, encouraging cooperation and communication, and fostering positive approaches to competitiveness. But it can often be an uphill battle when arguing in light of the many examples of the dysfunction of physical education in America. This post is not meant to argue that all physical education is well executed, nor meant to boast about my positive experiences, nor meant to invalidate any negative experiences people had in gym class. I am writing this post to share a positive example of physical education curriculum, and to open the door for discussions about how some of the principles and approaches in this one Physical Education exercise could be applied to other educational game endeavors, digital or otherwise. In this post I will recount my experiences with one specific game we played, and to make sure I got the details right, I got in touch with my teacher who designed the game.*

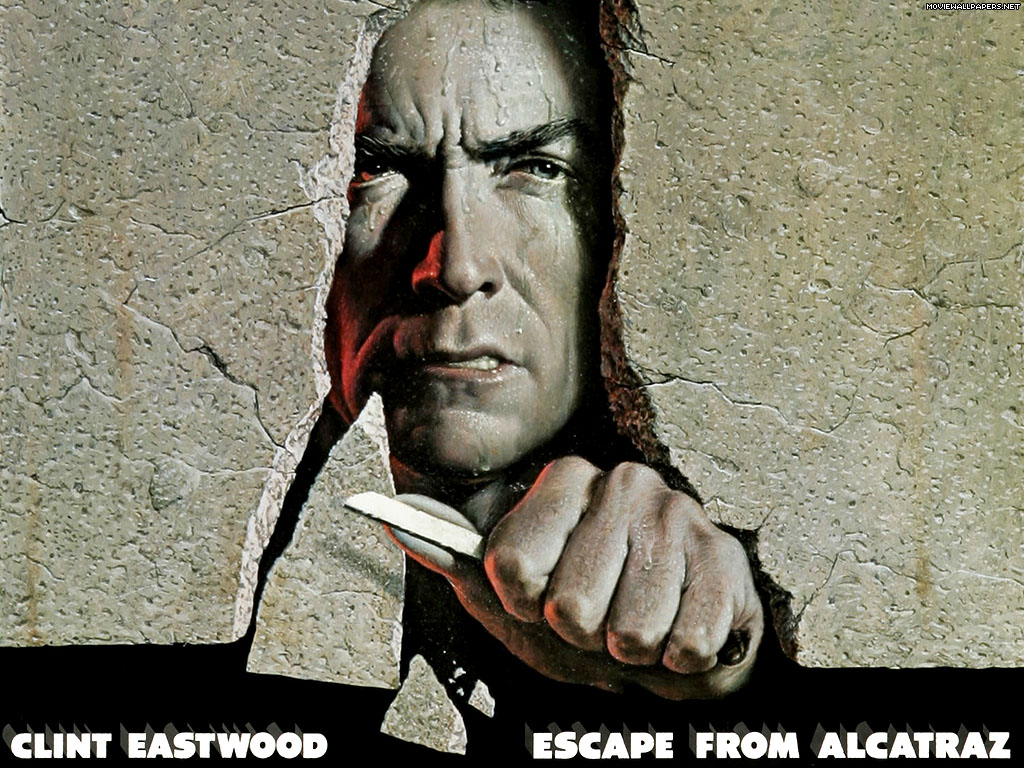

The game was called Escape from Alcatraz. In our gymnasium there was a second story wrestling room with a window that looked out onto the basketball floor. The window was pretty large and could be opened to leave about a 6 foot square opening. Below the window on the gym floor was placed a heavy mat, as would be used for catching a high-jumper, or a pole-vaulter in track and field. From the window was secured a heavy duty rope, extending almost to the mat on the floor. The class began in the wrestling room, and we students were told that we were all prisoners in Alcatraz, a high-security prison, and that we were planning our escape. Given that we were in prison, we could not talk or make too much noise, lest the guards (played by our teacher) should hear us trying to escape. The goal was for everyone in the class (approximately 20 students) to escape from Alcatraz, out the window and down the rope. This of course required teamwork and planning that all needed to be done with non-verbal communication. If, during descent, too loud a noise was made, all the prisoners were caught and the process would start anew. In my memory, there were some other parts of the escape as well — that once we had descended the entire team to the mat, there were some other challenges on the gym floor, like putting together an anagram puzzle to build a raft or something like that — but in neither my, nor Russ’ memory, could we put together the details around those parts. I would like to focus on the first part of the challenge, however, and what I think made it such a successful game.

I don’t think we ever accomplished our escape on the first try. Inevitably, we as high-schoolers, would get frustrated, make a noise, try to stretch the rules, and get caught, having to start over. These failures were valuable. No class would arrive with a perfect system of non-verbal communication, roles were not perfectly pre-established, and teamwork had not coalesced. It was through these failures to escape that all these patterns would emerge, as sign systems were developed for communicating, different leadership roles and abilities became apparent, and the team found itself. I think the non-verbal communication had another benefit as well, which is that it limited overt criticism which can so often ruin physical education experiences for those who become the focus of cruelty or ridicule. The goal was to get everyone out, and the silence limited the possibility of the cruel or vicious comment that might be hurled when someone makes a mistake. Sure people could still shoot glares, or at worst, perpetrate some kind of physical violence, but I’ve already painted a pretty clear picture of our teacher’s attentiveness, so I do not recall that happening. I also think it is significantly easier to offer positive encouragement than negative cajoling when you are charged with not making any noise. Seriously, silently shoving an unwilling participant into doing something doesn’t work. Of course students aught to know and be told that negativity is not an appropriate behavior, but the positive reinforcement of success gained through encouragement is important for nurturing that ethical behavior. We should know that simply telling someone they shouldn’t do something does not necessarily compel a change in behavior. I do think that Escape from Alcatraz did an excellent job of encouraging students into positive communication and cooperation through the constraint of silence.

Getting an entire class of students down a 10-foot rope silently is not easy, and it requires planning. Who goes down first? Who can help to spot and support people coming down? Who is strong enough to be the last one down? All of these questions needed to be answered and dealt with silently, and I think this is part fo the genius of the game. So long as you can get buy-in from the class around the collective goal of getting the entire team out, there has to be teamwork and collaboration. There is not much room in the game for any one person to “sit-out” or not be involved. Furthermore, the challenge requires people with different abilities and strengths to use those to an advantage. A smaller student, who may have been disadvantaged in a game of basketball, for example, might be the most valuable person for going down the rope and escaping silently first. A heavier but stronger participant might need to help others down the rope and then rely on the support of peers at the end to silently descend. The game did a nice job of encouraging different types of students to discover what they could lend to the cooperative escape effort.

It is one small positive example among many negative ones out there, but I did think it would be useful to recount an example of a fairly simple, but creative game used in a physical education class that I think did an excellent job promoting many of the positive educational benefits of games. I know, I know. I was lucky. Thanks Russ.

*In addition to being my Physical Education teacher, Russ Enlow is the father of one of my best friends, and I have known him since I was five years-old. He is a dear friend, and we stay in touch. In fact, I currently have a six point lead over his fantasy baseball team in our yearly league, and I never fail to remind him that I hope all of his players end up hurt.