Take The Risk

When I first volunteered to write a blog post, I had this marvelous idea: I was going to lay out a series of easy tips on how to increase diversity in your game design. My mental image of it was maybe a little extravagant, and maybe fueled a bit by how I view the relationship between “professional” game design and what game academics and critics have to offer that. I really did think it would be great if I could answer that seemingly all-important call for “practical” advice, where what game devs really want are concrete steps they can take during their process to put these pie-in-the-sky ideas we scholars dig up into everyday use. I’m being a little flippant there, but this isn’t 100% far from the truth. And so I thought, yeah: I have an investment in games being more diverse, and media representation is one of my areas of expertise. I can do this. I’ll do a top ten list! Simple things you can do to help make a more diverse game.

The truth is, when I went to write that very blog post this past week, it was hard. Much harder than I’d imagined, and not for lack of ideas for the “tips.” I had plenty of those. I even went to Twitter and asked others for their thoughts on what those tips should be… and since this post has ended up heading in a different direction, let me thank those people who responded right now. I appreciate you sharing those thoughts with me. But it was the “hey, let’s turn this into a practical step” effort that was tripping me up. And the more I wrote, and the more examples I tried to write, the more self-doubt was coloring my process. What was I doing? Who was this helping?

I spent some time reflecting on my doubts and I think I’m going to answer my own question in the form of this revised post.

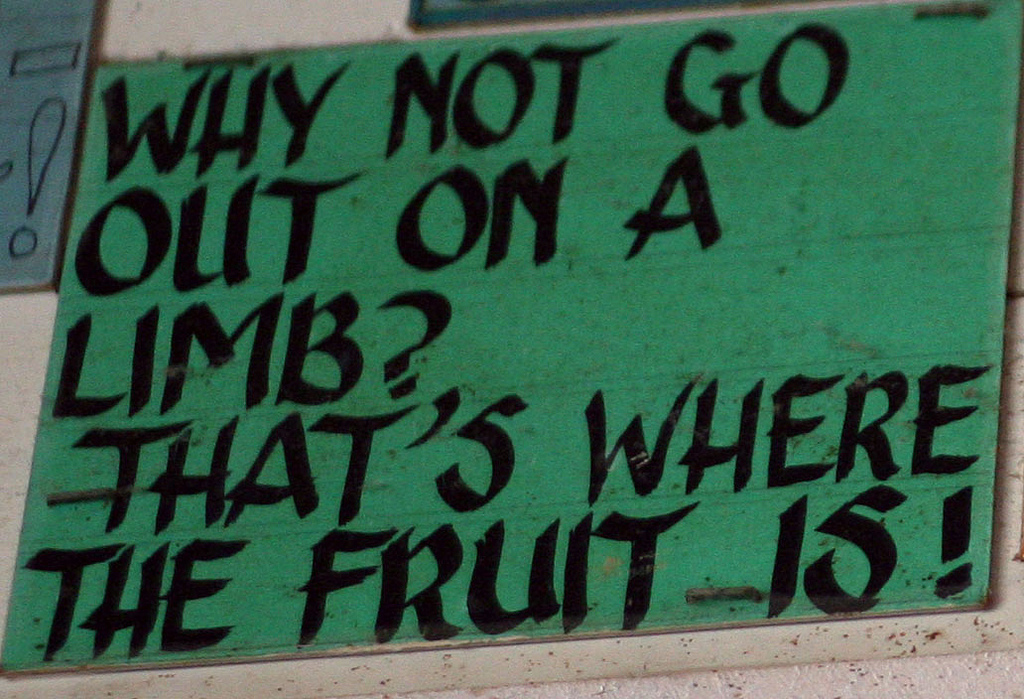

To start, I’ll share the very first tip I wrote with you: “Take the risk.” I still stand behind this one. In any sort of media creation — TV, games, movies, whatever — including things that don’t match up to the power structures of the day is perceived as a risk. It’s a risk that comes from an imagined audience, a perceived culture; sometimes those imagined things are conjured through numbers that market research provides us and sometimes they come from inside our own heads as people who live in the world. “Hegemony” as a Marxist term refers to a power structure that is constructed through consent, after all. If we think the world is full of cisgendered middle class straight white Christians then creating something that they might not like — and thus might not “buy” for multiple definitions of the term — is “risky.” You might not recoup your investment. I hasten to add that, rhetorically, the opposite of this situation is “safe,” as in “a safe bet.”

What I realized as I wrote was that I was trying to find a way for game developers — people often working in the extremes of finances, either struggling to produce with little to no funds or being responsible for untold amounts of production capital — to “be more diverse” without taking too much risk. My very first commandment was to encourage people to step outside their comfort zones and then everything I wrote seemed like it was encouraging people to do that in very safe, very controlled ways. I was betraying my own principle from the get go, effectively saying “Take a risk! But safely.”

Now, I personally have a relatively conservative personality. I’m more inclined to compromise than to be a radical and I have an attachment to the idea of balance, e.g. that we need a little of [x] and a little of [y] and that complementary opposition is philosophically and culturally valuable. I’m saying all this because I think it explains why I was doing this awful thing I just described. But hilariously, I was stopping myself coming from the other direction, too. I wanted to reference some queer games critiques and texts and held back for fear of upsetting them. I myself have no small amount of privilege — I identify as a cisgendered male, I’m white, I’m middle-class and able-bodied — and I began to wonder if that was keeping me from seeing the big picture. I became so concerned with not upsetting anyone too much that I was shying away from the mission of the thing that I had set out to do.

Does this sound like a familiar scenario?

I hope that when friends and colleagues in both academia and the industry read this, they’ll forgive my excesses, but the revised version of my original plan for this post is: Suck it up and take the risk.

I can hear the objections now: “But the market won’t support that!” “I’m not sure I can do it right; I’m worried about offending someone.” “You haven’t made a game/you’re not in the business; you don’t understand the process. It’s not that simple.”

I am here to tell you that the people you are not representing do not particularly care that making diverse games is risky or hard, because in ways both big and small, BEING those people is risky and/or hard. Having to hide/lie about your gender or sexuality to avoid abuse, being a woman living terrified everyday in a patriarchial rape culture, being a person of color denied opportunities in all realms of life solely on the basis of ethnicity or background… these are not easy. Navigating the world of privilege is risky and the distance you can fall is steep indeed.

More to the point, when I see these objections, I have to ask: how bad do you want it? Are you interested in making a woman or a person of color the hero of your action-platformer game, but only up to the point that someone in marketing says no? If that’s the case, I’d ask you to re-evaluate your commitment to the idea. This is maybe a stereotyped example, but I chose it precisely for its illustrative properties. At some point, if you are interested — REALLY INTERESTED — in adding diversity to your game then you are going to have to fight for it. You are going to have to tell people who want to take the safe bet that the “risk” is the better option, and I’m using the Quotes of Dubiousness on the word “risk” for a reason.

If you’re asking yourself “How do I do this, though?” then I’m going to ask in return: how would you fight for ANY risky, controversial idea? Think for five seconds about the last time you had an idea that you knew wasn’t going to be popular, but which you were excited and passionate for. You did some research, you talked your ideas over with people, you molded it and shaped it and then you brought it to a meeting and with every ounce of that passion for your risky idea you sold people on it. You made them believe.

Well, guess what: that’s what you’ve got to do here, too. You’ve got to have some of that passion. You’ve got to believe in the moral good. If you don’t, then you’re going to get hedged into taking the safe bet every time, and the story of this blog post is proof of that. The passion I needed to make a statement wasn’t with my original plan, and once I found it again the shape of this blog post changed. And more to the point, think about what’s worth fighting for. If you’re willing to go to bat with your dev team and upper management for six new sexy alternte DLC costumes for minor NPCs but give up at the first sign of resistance to having a non-awful major transgender character, I admit some concern about your priorities.

The world is changing. Gaming is changing. The markets are certainly changing, if that’s your thing. The massive groundswell of advocacy and diversity efforts that arose at GDC this year, events like the recently-held Different Games conference… they are proof that this imagined world that creates the “safe bet” is a phantom, a dying echo. This is the perfect time for people with passion to take the risks that I’m talking about, to prove that this imagined lie we’ve been catering to for so long is nothing BUT a lie. But you’ve got to want it. You’ve got to believe in it, because that’s what powers the fight. And you will have to fight, but it will be worth it.

I don’t have 10 easy tips to give you because there is no such list. There is only the commandment to take the risk, to gather up your passion and your courage and to fight back against the safe bet. It is difficult and sometimes you will stumble and fail and sometimes you will offend and you know, that’s fine. The important thing is that every time you fight the fight, every time you put yourself on the line for the ideal, that line that determines what’s a safe bet and what’s a risk gets pushed just a little farther forward… and that’s a goal worth accomplishing.