Making Good Things: Some Comments on Independent Games

As a former lead game design for Magic: The Gathering, I was recently invited to serve as a featured curator for the analog side of Boston Festival of Independent Games. Over the course of this process—as well as in the weeks leading up to it—I had the chance to observe or play almost a dozen games submitted to the Festival for competition.

As a former lead game design for Magic: The Gathering, I was recently invited to serve as a featured curator for the analog side of Boston Festival of Independent Games. Over the course of this process—as well as in the weeks leading up to it—I had the chance to observe or play almost a dozen games submitted to the Festival for competition.

This ruled. It turns out that twenty-four hours of nonstop gaming plus a couple choice pie + PBR specials at a certain Davis Square pizzeria makes for a decent weekend. Who would have thought?

I’m assuming, though, that most of y’all reading this here blog aren’t reading it to hear about my revels and revelations. You want to learn about games. You want to learn about making games. You want—I hope—to learn specifically about how to make good games. As such, I’m going to take a few moments to distill (drumroll, please) my three most salient lessons culled from curating an indie games festival.

Write that one down for posterity.

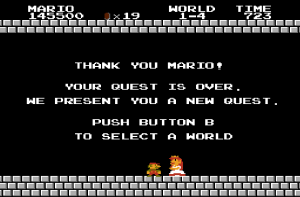

3. Make Sure Your Game Ends

It’s a bummer, really, that the properly-articulated title of this segment is more of a mouthful: make sure your game ends in a satisfying way when played by skillful players. But it’s true: no fewer than three different games I played were impossible to actually resolve under the stated set of rules.

It’s a bummer, really, that the properly-articulated title of this segment is more of a mouthful: make sure your game ends in a satisfying way when played by skillful players. But it’s true: no fewer than three different games I played were impossible to actually resolve under the stated set of rules.

On one level, of course, you want to make sure you’ve actually planned out a viable narrative progression of your game. This typically involves envisioning what the end game looks like and working backwards to figure out how to progress through your middle and early phases. In fact, the most successful games proceeded in such a way that they definitionally needed to end after N turns or N consecutive actions, even if that inevitability was masked in one way or another (a great example was a castle-building tile game that ended once you placed all the very-cute-looking flag-and-roof tiles for each of the game’s races—which was intuitive, as every building obviously needs a roof!)

But for more tactically-advanced games, what we found happened was that the game resolved on the first couple of plays through—but once we found out what was going on, we were able to prolong the game state indefinitely. This problem is most salient for tactics-style games where all the players involve start with equivalent resources on a balanced game-board. Usually, this problem occurred because:

a) Players were not required to move game pieces;

b) Players were able to move pieces in multiple directions from the beginning of the game. Less operative to this point than the literal direction of piece-movement is the fact that the game didn’t proceed along a linear narrative;

c) Pieces could not ‘level up’–that is, what you started out with was what you got. Either you cycled through a set of similar cards, or you revealed a set of similar tiles, or your board was populated with pieces that remained essentially the same on the first turn as they did on the second. This in turn makes it very easy to achieve parity;

d) Certain required victory conditions could be ‘stalemated’ or rendered impossible.

Ultimately, nothing is going to guarantee this issue is resolved except for a lot of playtesting. However, any of the four factors I just mentioned should serve as a warning-sign for a game that ultimately may never achieve resolution. This is precisely what you don’t want should you go to print, because you’d just be hemorrhaging replayability.

2. Make Sure It’s Someone’s Job to Try and ‘Break’ Your System

For much of my time on Magic, I worked as a ‘developer’. This word has a lot of baggage—to take just one example, I can’t program anything—but I do like the term ‘development’ better than (for example) ‘balance’. ‘Balance’ implies that things are okay as long as nobody has an edge, but really what you’re trying to do is ensure that the relative power level of your game’s component parts culminates in an experience that is ultimately fun.

For much of my time on Magic, I worked as a ‘developer’. This word has a lot of baggage—to take just one example, I can’t program anything—but I do like the term ‘development’ better than (for example) ‘balance’. ‘Balance’ implies that things are okay as long as nobody has an edge, but really what you’re trying to do is ensure that the relative power level of your game’s component parts culminates in an experience that is ultimately fun.

What this means is that while nothing may be ‘imbalanced’, certain variables start to become the only things that matter once you’ve decided to begin pursuing a given strategy. This is great when it leads to simplicity and an intuitive pattern of play, but is a major drawback when you’re counting on a game’s strategic richness to be its key selling point.

Another issue arises when a game features a mechanic that is likely to be used to gain advantage in counterintuitive—or ultimately ‘cheesy’ and ‘bad-feeling’–ways. As an example, one game I played (which was excellent overall) allowed any player to activate a timer at any point. When the timer ran out, the game would end. The game’s rules stated that whoever activated the timer would receive an additional victory point at the end of the game.

Now, this seems all fine and dandy until you realize that the ‘correct’ play is to always immediately activate the timer at the very beginning of the match. You and your opponent are playing the same game by the same rules, only you start out +1 point!

I bring this example up because on the surface it seems like a cool, unique, interactive way to bring about the end game: choosing when to ‘ping’ the clock becomes an interesting strategic choice, as both players try to analyze how and why they have an edge. Unfortunately, when someone comes in to play competitively, he or she realizes that because the ultimate result is zero-sum, it’s ‘correct’ to kick things off on unequal footing.

The idea here is that a ‘breaker’ can do a lot more than achieve ‘balance’: he or she can make sure that the mechanics you’ve designed are actually serving their intended purpose!

1. Make Sure Your Game is Fun

Okay. This is a cheaty answer. Obviously, everybody is going to try and make a fun game, and the whole concept of ‘fun’ is (I realize) so nebulous as to mean a thousand different things to a thousand different people. So isn’t saying ‘make your game fun!’ kind of like saying ‘make your novel good’?

I would argue that it’s not. Here is the thing: as game designers, we’re heavily, heavily invested in the system we’ve created. We’ve spent countless hours crunching numbers, deriving play patterns, brainstorming components and mechanics, etc. We probably came up with our concept in a day or so, and spent the bulk of the time thereafter making sure we got the details right. So it’s only natural that—having been bogged down in the details for several months—we forget to surface and take a look again at the product holistically.

Doing so is absolutely essential, though. People want to purchase games, not complex dynamic systems of opt-in variable-rate equations. There were three or four games I played that seemed to do everything right, but that just weren’t very compelling at the end of the day. If they were on my shelf, I’d never bust them out to the exclusion of other games.

What’s important, I think, is to pay keen attention to the experience: what are you offering the player that other games are not? Is it unparalleled strategic richness? Is it the thrill of engaging competition? Is it a compelling opportunity for a player to express his or her latent creativity? Whatever the answer is, you’re going to want to be able to say in a sentence or two why you’re doing that better than the other games on the market. This isn’t just for economic reasons—you owe it to your game out of respect for your players! You’re making a claim that the thing you’re creating is worth their time. They could play any other game on Earth, and they’re choosing to play yours. That’s a huge amount of trust.

So what’s the payoff?